France has been trying to protect cheese names for almost 100 years

Since the early 20th century, a system called Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC) has provided legal protection to hundreds of French products that are made in very specific ways and places. They have a similar system in Italy called DOC (these systems are also referred to as AOP and DOP, but that’s another story). AOC protects everything from wine (Châteauneuf-du-Pape was the first designation) to lentils to heritage breed chickens like poulet de Bresse. The first of 46 French cheeses to win AOC status was Roquefort, way back in 1925. AOC regulations specify where a cheese can be made, but they also lay out a sort of recipe that must be followed if the product is to bear the authentic name.

The “recipe” for Roquefort (which, like all AOC protected cheeses, is presented on a French government website) indicates the breed of sheep that must be used, where those sheep can graze, for how long and in what specific cave the cheese must be aged. Why? Because all of those factors influence the taste of the resulting cheese. People making blue cheese from cows’ milk in Wisconsin are not allowed to call it Roquefort. If they do, the INAO will come after them.

American cheese companies have been duping consumers for decades

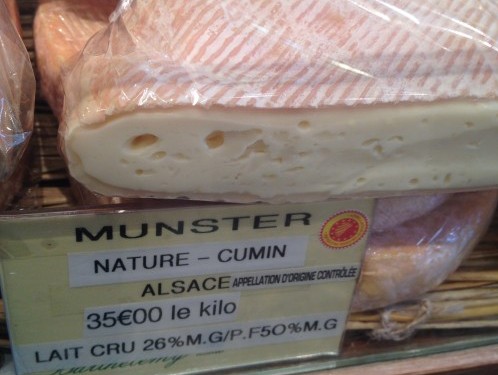

Two AOC protected washed rind cheeses. From left: Epoisses & Munster

Another trick is to drop (the protected) part of the name, turning Brie de Meaux and Camembert de Normandie into plain old brie and camembert. And plain they are. Brie and camembert sold in the US are pasteurized, bearing virtually no resemblance to their raw milk counterparts in France. American health regulations, which are quite different than those in other countries, insist that cheeses that have been aged for less than 60 days must be made from pasteurized milk. The AOC regulations of Brie de Meaux and Camembert de Normandie specify that these must be made from raw milk and aged for specific periods that are in both cases less than 60 days. In other words, the authentic product cannot legally be sold in the US. It is only possible to sell an adulterated version and to tweak the name.

But wait – French cheese companies are also doing it…

Here’s the thing: industrial cheese makers are duping people in France, too. Pasteurized brie and camembert are not only produced for export, they are also sold all over France. Because they are cheaper to make (from the milk of cows who produce a higher volume of less delicious milk after feeding on inferior fodder), and because they are pasteurized and therefore shelf-stable, they can be sold at lower prices from supermarkets that lack the space and staff to properly care for and sell raw milk cheeses.

A pasteurized industrial brie produced in France tastes like a pasteurized industrial brie produced in Wisconsin. Neither one tastes anything like a real Brie de Meaux. The factors that make the protected raw milk cheese so special – the effect of terroir – are no longer present, so frankly it doesn’t matter where the factory is located.

From left to right: industrial pasteurized brie & artisanal raw milk Brie de Meaux

Artisanal vs. Industrial, not Europe vs. America

The proposed changes would force American producers of brie to instead label their cheese as a “brie style” cheese, or to come up with a different name altogether, like bryee or br$e. The same is true for fake Parmesan and a host of other knock-off cheeses. Predictably, the people who are most vigorously lobbying against the proposed restrictions are industrial cheese makers who produce billions of dollars worth of gas station quality cheese. Also predictably, the media has cast this as an act of European aggression/snobbery against American cheese makers.

That’s unfortunate, because there are so many wonderful producers of artisanal cheese in America. They’re not the ones protesting these restrictions. These rules wouldn’t hurt somebody like Uplands in Wisconsin, who produce an incredible cheese that I sampled during my last trip to the States. Uplands will tell you on their website that it is made in the tradition of a French Beaufort, but they have come up with their own name – Pleasant Ridge Reserve – referring to the green pastures where their cows graze during the months (May-October) when the cheese is produced. These aren’t the farmers who are making a stink about the proposed restrictions. Rather, it is their factory neighbors, and the lobbyists who represent them, who want to name their processed cheese bricks after something that is produced in an altogether different way.

As someone who cares about seeking out and celebrating special products, I think labels are very important. We need specificity in naming in order to distinguish outstanding from good from mediocre. So of course I support the proposed restrictions that would prevent cheese makers in America from using protected AOC cheese names to promote their industrial products. I only wish that France would apply the same pressure to industrial cheese makers within its own borders. Lactalis, the world’s biggest producer of industrial cheese and the greatest threat to authentic raw milk Camembert, is not located in Wisconsin.

Additional Reading

- Europe Wants Its Parmesan Back, Seeks Name Change (Associated Press)

- Europe Tells U.S. To Lay Off Brie And Get Its Own Cheese Names (National Public Radio)

- Say bye bye to parmesan, muenster and feta: Europe wants its cheese back (The Guardian)

- Europe’s War on American Cheese (Time)

- Let them eat ‘feta’: why the EU should allow US cheesemongers to steal names (Liz Thorpe in The Guardian)